How do we get our gut flora?

by Gutsy Flora

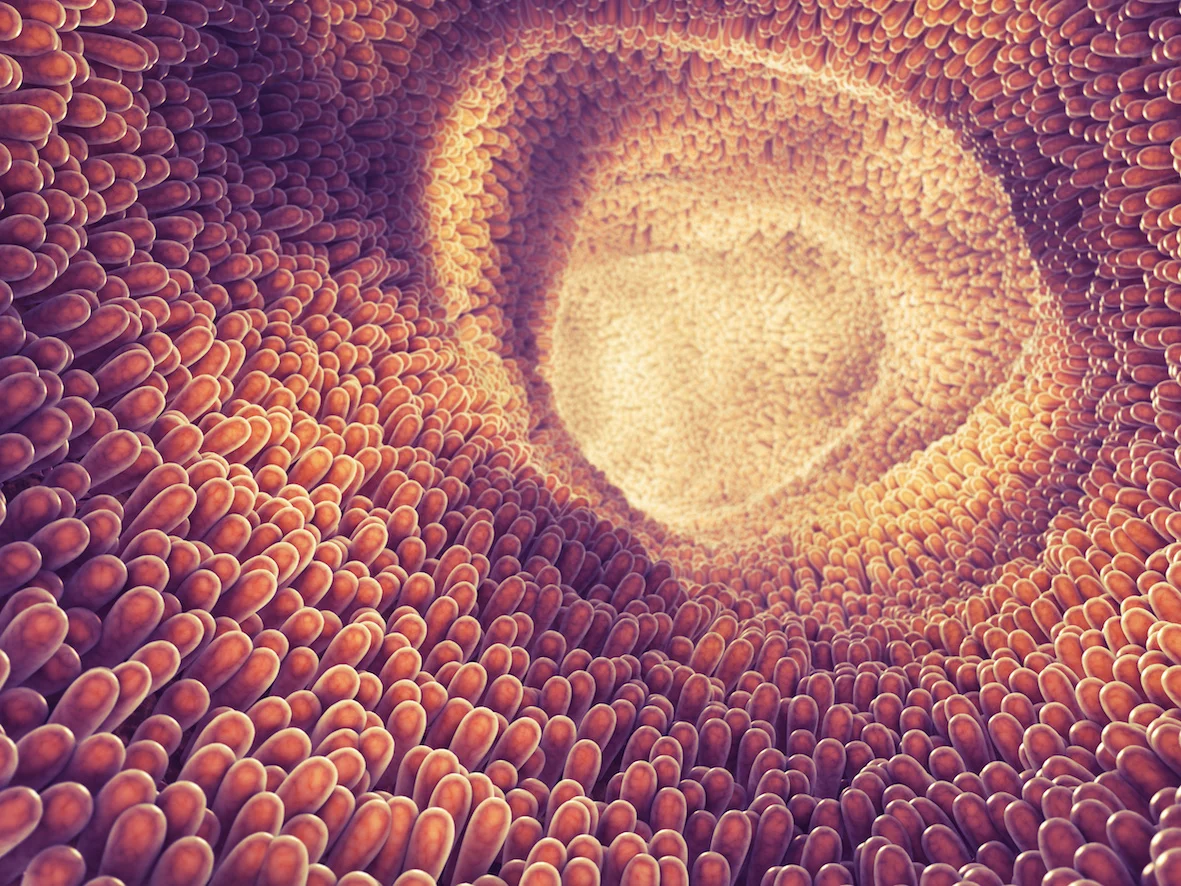

We share our bodies with several hundred microbial species...

WE ARE SUPER-ORGANISMS

Current estimates suggest that we each possess roughly 38 trillion bacterial cells on our body’s surfaces. Compared to the 30 trillion human cells, this puts the ratio of microbes to your human body cells at a little greater than 1:1 – in favour of the microbes!

Imagine yourself as a fluffy swarm of bacteria on legs. A parallel universe living inside of our bodies. Freaked out yet?

Whilst most of these inhabitants are beneficial or harmless, a tiny number of them are unwanted and pathogenic. Important for the production of some nutrients and vitamins, drugs, modification of gut surfaces and training of the immune system (amongst other things), these organisms are in constant communication with our bodies through the superficial linings of their respective organs. Yet when the delicate microbiome is knocked out of balance – or gains entry to other areas of the body, poor health kicks in. (See references below 2-8)

So, how do we get this microbiome in the first place?

BIRTH + VAGINAL SEEDING

We are essentially totally sterile in our mother’s womb. Or so we thought. Though still contentious, recent studies are suggesting that gut colonization may begin before birth, in the womb.

Then, through the act of birth, the newborn is inoculated with microbes through passage down the vaginal canal before gathering microbes from its environment; the doctor’s gloved hands, our mother’s skin, the bedding and clothing. We know that microbes are then detected in an infant first poop.

Together, these pioneer species put into place the building blocks needed for a fully-functioning microbiome.

This process does not occur in caesarean section births wherein the infant evades passage through the birth canal so microbes from this region are not encountered, and microbes that survive the sterile cleansing of the maternal skin are met instead. Caesarean-born infants (who are significantly higher risk of allergic disease) typically begin life with a microbiome more similar to that of the maternal skin microbiome (than vaginally born infants) and differences in make-up between modes of delivery have persisted up to 7 years into life. To counteract these differences in microbial profile, a process known as vaginal seeding has emerged in which vaginal fluids that contain vaginal microbes are applied to a newborn child born by C-section in a process of artificial inoculation. This is done in order to replicate the colonisation that occurs as a result of vaginal birth. Whilst it has been shown in a small study that vaginal microbes can be partially restored to C-section delivered babies via this technique, concerns have been raised that the little evidence that exists to support this trend is insufficient to outweigh its risks – such as colonisation by pathogenic species. There remains much speculation, namely whether the process is effective at priming the immune system, whether it confers lasting colonisation and in which individuals the swab would be beneficial. The process is therefore not currently recommended. Instead, other contact is encouraged postnatally, which can encourage sharing of microbiota and early breast feeding.

THE FIRST FEW YEARS

It only takes between one and three years for a gut flora of an adult’s maturity to become established and this window of colonisation crafts the microbial landscape leading into adult life. Within this time, pivotal interactions and experiences will occur. These include the initial mode of birth, breast vs. formula feeding, antibiotic use and an increasing interaction of an infant and it's environment.

BREAST IS BEST FOR GUT HEALTH

Nature’s best, our good friend, breast milk has an important role to play. Rich in short chain fatty acids, special sugars, beneficial bifidobacteria and leukocytes; helping to craft this growing microbial community into something useful.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE GUT

Like much else, the gut microbiome may well be most malleable in early life. Pets, cleanliness (or lack of!), diet and pre/probiotics all contribute to establishing the busy ecosystem of the gut. And, like any great rainforest, it must be carefully maintained. In practice, this means supporting a diverse and well-populated gut tract; the microbial populations of our body surfaces are constantly evolving throughout life, even after the formative years of early childhood.

This spells out a need to return to the outdoors and re-connect with the microbial ecosystem that surrounds us. After developing over a few hundred of thousand years in unison with the human host, the relatively rapid shift to the sterile, ultra-clean urban environment that has taken place over a few hundred years has been dramatic in the eyes of the microflora. Whilst we have crafted our surroundings to suit our needs, we have overlooked the needs of our microbiome. As a consequence, colonization and growth has been hindered and the healthy microscopic guests that call our gut home are being displaced by their damaging and more resilient cousins.

We could attempt to limit impact of modern living on the microbiome by spending more time outdoors, practicing natural processes such as vaginal birth, breast feeding and other intimate interactions that involve close contact– even kissing! The body will likely welcome a shift away from the fastidious, ultra-clean, man-made environments of their schools, hospitals, homes and cars. Whist this doesn’t mean a return to the somewhat outdated practices of mothers pre-chewing their baby’s food, the key is to keep their diet diverse with lots of prebiotic and probiotic building foods and to allow more room for outdoor fun; tree bathing (that’s also a thing!) and chasing squirrels in the park could quite possibly be the new health trend… don’t joke, I can see it now….

References

1. Sender R, Fuchs S and Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002533.

2. Levy M, Thaiss CA and Elinav E. Metabolites: messengers between the microbiota and the immune system. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1589-97.

3. Clarke G, Stilling RM, Kennedy PJ, Stanton C, Cryan JF and Dinan TG. Minireview: Gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:1221-38.

4. Willey JM, Sherwood L and Woolverton CJ. Prescott's microbiology. Ninth edition. ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2014.

5. Sousa T, Paterson R, Moore V, Carlsson A, Abrahamsson B and Basit AW. The gastrointestinal microbiota as a site for the biotransformation of drugs. Int J Pharmaceut. 2008;363:1-25.

6. Faderl M, Noti M, Corazza N and Mueller C. Keeping bugs in check: The mucus layer as a critical component in maintaining intestinal homeostasis. IUBMB Life. 2015;67:275-85.

7. Sommer F and Backhed F. The gut microbiota--masters of host development and physiology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:227-38.

8. Peterson LW and Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:141-53.

9. Perez-Munoz ME, Arrieta MC, Ramer-Tait AE and Walter J. A critical assessment of the "sterile womb" and "in utero colonization" hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome. Microbiome. 2017;5.

10. Adlerberth I and Wold AE. Establishment of the gut microbiota in Western infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:229-238.

11. Renz-Polster H, David MR, Buist AS, Vollmer WM, O'Connor EA, Frazier EA and Wall MA. Caesarean section delivery and the risk of allergic disorders in childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1466-72.

12. Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N and Knight R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11971-5.

13. Fujimura KE and Lynch SV. Microbiota in allergy and asthma and the emerging relationship with the gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:592-602.

14. Salminen S, Gibson GR, McCartney AL and Isolauri E. Influence of mode of delivery on gut microbiota composition in seven year old children. Gut. 2004;53:1388-9.

15. Dahlen HG, Downe S, Wright ML, Kennedy HP and Taylor JY. Childbirth and consequent atopic disease: emerging evidence on epigenetic effects based on the hygiene and EPIIC hypotheses. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:4.

16. Dominguez-Bello MG, De Jesus-Laboy KM, Shen N, Cox LM, Amir A, Gonzalez A, Bokulich NA, Song SJ, Hoashi M, Rivera-Vinas JI, Mendez K, Knight R and Clemente JC. Partial restoration of the microbiota of cesarean-born infants via vaginal microbial transfer. Nat Med. 2016;22:250-3.

17. Cunnington AJ, Sim K, Deierl A, Kroll JS, Brannigan E and Darby J. "Vaginal seeding" of infants born by caesarean section. BMJ. 2016;352:i227.

18. Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R and Gordon JI. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222-7.

19. Bertotto A, Castellucci G, Fabietti G, Scalise F and Vaccaro R. Lymphocytes bearing the T cell receptor gamma delta in human breast milk. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:1274-5.

20. Jenness R. The composition of human milk. Semin Perinatol. 1979;3:225-39.

21. Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299:1259-60.

22. Mangiola F, Ianiro G, Franceschi F, Fagiuoli S, Gasbarrini G and Gasbarrini A. Gut microbiota in autism and mood disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:361-8.

CREDIT

Chef and Health Consultant Gutsy Flora is on a mission to absorb and share everything she loves about Gut Health. A topic she is desperately trying to keep up with and is dedicated to the cause of translating information for the Gutsy readers. Her expertise are in fermenting and supporting people to lead a holistic lifestyle. Her favourite topics of interest are the gut-brain-axis and whole foods relating to the gut microbiome. Flora works with private clients to inspire and guide them in making truly sustainable adjustments towards a healthier balance that suite their lifestyle.

Written by © Flora Montgomery. All rights reserved.